Listen to the Podcast!

This fall, the Giants and the Dodgers will face each other in the postseason for the first time, ever, in their 138 year history.

Well…sort of. Technically, yes, it’s their first postseason matchup. But not really.

The Giants and Dodgers have met before in playoff games. Of course, you’ve heard and seen the “Giants win the Pennant” call from 1951, where the Giants beat the Dodgers in a tiebreaker series to determine the champion of the National League. They did the same thing in 1962 as well, winning another tiebreaker series. But both of those were before there was a National League Championship Series, and MLB considers those games just additional regular season games, as they do for tiebreakers today. So they have been in playoffs, just not THE playoffs.

But as we approach this year’s historic matchup, it’s worth looking at one other matchup these two teams had, a long time ago, that most people don’t remember. Heck, it was before one team had the name we know today.

If you want the TL:DR, it happened in 1889. The Giants and the Brooklyn team we now call the Dodgers faced off in the World’s Series. The Giants won, six games to three, in a best-of-eleven series. So, if you’re focused on wins and losses, there you go. I’ve saved you many paragraphs of reading about this.

But the truth is, that matchup was about more than just which team won. It was the culmination of a series of events that led to the creation of both teams; a series of events that also helped define baseball today.

And while the series between the Giants and would-be Dodgers would not end the turbulence that professional baseball faced, it was the culmination of an era that set the foundation of baseball that we know today.

So, allow me to share you the story. It’s a story about rivals. Not just the teams in Manhattan and Brooklyn, but rivalries between the owners and players; between different leagues; between two cities separated by the East River, and between the biggest cities and all the rest of them. It’s the story of how professional baseball began.

It’s the story of the birth of the Giants and the Dodgers.

*****

To understand this story, we need to start at the beginning. The VERY beginning.

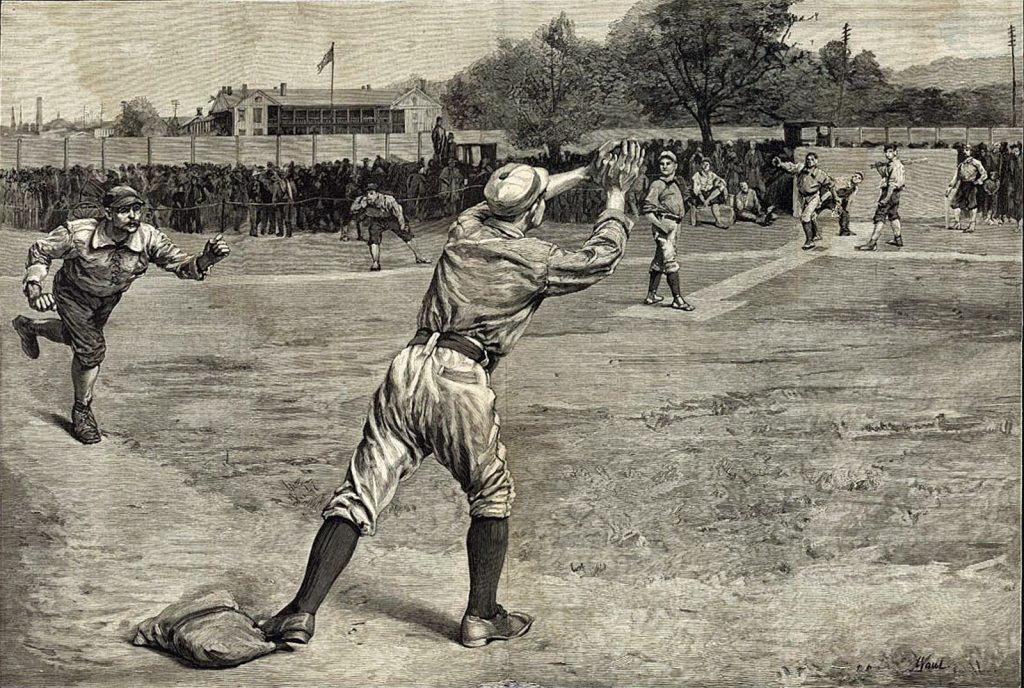

Baseball in the late 1800’s looked very different than the sport we know today. Pitchers threw underhand. Fields generally were not enclosed with fences, so balls to the outfield would roll and roll. It’s not like most games had fans out there. The home team got to choose who bat first, rather than it always being the visitors. They didn’t sing “Take Me Out To The Ballgame” in the middle of the 7th inning…since it hadn’t been written yet. There were no lights, so games often got called for darkness. And championships were determined by the record in the regular season. There were no playoffs.

Baseball’s first serious attempt at a professional organization was less like a league and more like a gaming club. It was named the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, but it was usually just called the National Association. Note that this was an association of players, however.

Starting play in 1871, things were run very loosely, with not many standards. Gamblers ran roughshod through the league, with its low payrolls. Teams would come and go. Over just five years of existence, 24 different teams were in the Association. Twelve appeared for just one year. Not every team survived a season. Only three played all five seasons the National Association survived.

One of those teams played in one of baseball’s first great baseball fields. The Mutual Base Ball Club of New York played in the Union Grounds, which was one of the first fully enclosed ballparks in the country, and one of the first stadiums for professional clubs. What it was not, however, was in New York City.

The Union Grounds sat in Brooklyn, which in the 1870s was an independent city, separated from Manhattan by the East River with no bridges. The Mutual never actually played in New York, having originally played in New Jersey before going to Brooklyn. No professional baseball team played on the crowded island of Manhattan as professional baseball was beginning. Both the park and the team were owned by William Cammeyer.

But what Manhattan was missing, Brooklyn enjoyed. The Union Grounds housed a few different teams along with the Mutuals over the National Association’s lifespan, including the Eckford Club and the Atlantic Club and, at one point, the Chicago White Stockings (for one game after their home was lost in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871). The Mutuals, however, were the only team to stay all five years in the National Association.

The Mutuals simultaneously were part of two of the three largest markets in the country. In 1870, one year before the NA was founded, New York held 942,292 people, while Philadelphia was the second largest city with a population of 674,022. Brooklyn came in third, with 396,099 people. Not surprisingly, one of the other two teams to survive all five years of the NA was The Athletic Club of Philadelphia. The fourth biggest city in the country at the time, St. Louis, only had 310,864 people.

(The third team that lasted all five seasons was the Boston Red Stockings, who won the NA four of its five years, but they aren’t important to this story. Sorry, Boston!)

The Association had many problems, but an important one was that some teams were not showing up to play games. While the big eastern cities had the fans to survive, many of the smaller western cities (like Keokuk, Iowa, who had a 1870 population of 12,766) struggled to get enough fans to pay to attend.

In those days, there were no playoffs. The league champion was decided by regular season record, and that was it. So if a team was out of it late in the season, they might not find it profitable to take a trip out west. Even in bigger cities like St. Louis, eastern clubs like New York and Philadelphia would beg off the road trips, citing their own financial hardships, and leave those western teams with games that had tickets sold in a lurch with their fans.

The National Association folded after 1875, but Chicago White Stockings owner William Hulbert thought he could do better. And so, just a year later, the National League was born in 1876 under his leadership.

Taking some of the stronger teams of the National Association, like Philadelphia and New York, alongside a few new teams, the National League was founded with eight teams. Hulbert founded the league with a stronger central control. He wanted to try to eliminate “revolving”, the free agency that saw players jump from team to team and made building a team harder, and he intended to create a league that saw more parity. Hulbert, as an owner from a Western city, also had a distrust of some of the big city eastern clubs, and that suspicion was well-founded.

Hulbert set down strong rules. New teams could only be in cities with a minimum population of 75,000, although even that could be overruled, as it was in the case of Hartford, CT, in the initial season. Hubert believed in morality, and he wanted to draw more mature and higher society fans, frowning on the boorish behavior that some fans and players exhibited. Gambling was not to be tolerated. He was also strictly moral, banning alcohol at the ballpark, and eliminating Sunday games, despite them having the best attendance. Ticket prices were raised to .50¢, also forcing out a certain level of fan. But importantly, it was important that teams live up to their schedules. Professional baseball needed to prove its credibility.

In the league’s first season, the Philadelphia Athletics and the New York Mutuals, two clubs from the old National Association, refused to go west to visit Chicago and St. Louis. Despite playing in the country’s two biggest cities by far, they cited financial hardship, but perhaps they felt that the National League needed them more than they needed the National League.

Right or wrong, Hulbert needed baseball to have credibility. He likely was also motivated by the acts of the two teams in the National Association. Either way, New York and Philadelphia were expelled from the National League after the 1876 season.

*****

Over the next two years, the National League fielded just six teams, but attempted to expand in the following seasons. Baseball was still played in big cities like Chicago and Boston, but now was also in smaller cities like Indianapolis and Providence. Over its first 6 seasons, 15 different teams played in the league, with several disbanding and others kicked out for violating Hulbert’s ideals. Only two teams appeared every year from 1876 through 1882: Boston and Chicago.

For any hardships the big cities had, the smaller cities still had greater problems. For instance, Hartford (who required an exception to join the National League due to its smaller population) was struggling after just their first year. Though William Cammeyer, the now-former owner of the New York Mutual, no longer had a team in the NL, he still owned the historic Union Grounds ballpark in the country’s third largest city, Brooklyn. It was offered it to be the home of the Hartford team at a cost, and they accepted. So the Hartford Grays now played in an entirely other state, and became known jokingly as the “Brooklyn Hartfords”. Their owner, Morgan G Bulkeley, was disappointed in attendance even in the big city, and the cut being paid to the stadium owner. The Hartfords were disbanded a year later, and they were the last pro team to play in the Union Grounds.

Teams moved in and out of the National League. St. Louis, Providence, Milwaukee, Troy, and Syracuse were just some of the cities that housed teams, many of them for only short periods of time. But one team that left the National League changed everything: Cincinnati.

The Cincinnati team rented out its stadium on Sundays, much to Hulbert’s chagrin. They served beer at those Sunday games, which upset him worse. The owners openly fought with Hulbert and the rest of the National League. After the 1880 season, Hulbert arranged for Cincinnati to be ousted from the NL for its many violations, but the franchise did not go quietly. They began to gather other interested parties who wanted to play outside the National League’s restrictive rules.

In 1882, Cincinnati was one of six teams to form a new league, the American Association, also known as the Beer and Whiskey League. Along with Chris Von der Ahe of St. Louis, a saloon owner, and a remade Philadelphia Athletics team that had been expelled in 1876, the new Association was founded with a firm anti-Hulbert stance. Hulbert had passed away in April 1882, just before the start of that season, but the National League was about to face its most difficult test.

There were two professional baseball leagues about to clash for supremacy in 1882, but there was one huge hole in both those maps. Neither New York City and Brooklyn had teams in those leagues. However, it did not mean that baseball was entirely gone from there.

*****

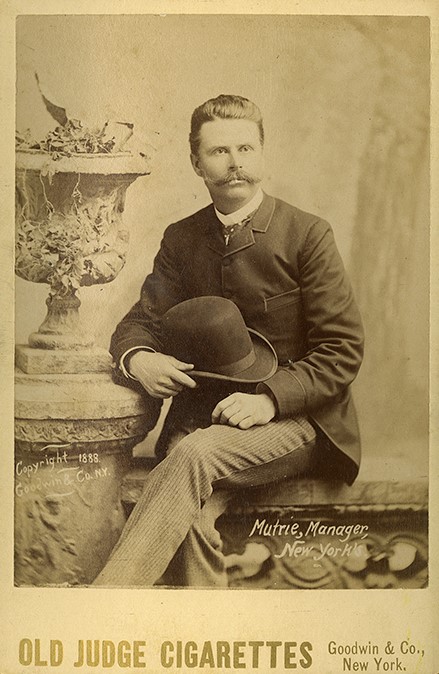

In 1879, the sun went down on the final game of the season for Brockton, Massachusetts, ending the game early, andleaving the team’s season, and the league championship in questio. But manager Jim Mutrie was trying not to let the sun set on his baseball career.

He was called “Truthful Jim” because he knew how to talk. People didn’t always know if he was telling the truth, but Jim Mutrie knew how to get people to listen.

Depending on the interviews he gave, he hadn’t played baseball before he was 20, or he was entertaining union soldiers playing baseball on Boston Commons as a young teen. That was the kind of person Jim Mutrie was. He claimed that on the Boston Commons, he became the first catcher to play up close to batters, because his game attracted so many fans, he had to do so.

Then again, when he began playing pro in 1875, his first season ended after one week because he took a foul tip that broke his collarbone, so maybe he actually was playing that close to batters in the days before catching pads and mitts.

In 1876, Mutrie was recruited by another young up-and-coming player, Bill McGunnigle to play for a team in Fall River, Massachusetts, that was collecting a lot of talent. Fall River played in one of the many leagues that came and went in the era, the New England Association. Mutrie came in as a shortstop, but when the team’s player captain/manager Sam Crane left the team midseason, it was Mutrie who was named the team’s new captain.

Over the next two years, Fall River had seven future Major Leaguers playing for them, and the team collected those players in unusual ways. In one game playing at Portland, Maine, the team Fall Rivers featured a towering left fielder named George Gore. In response, Mutrie recruited the star, and convinced him to join Fall River.

As tended to happen with teams of the day, however, players were lured away with promises of more money or other perks, and much of Fall River’s roster was gone by 1878. McGunnigle moved on to Buffalo, a soon-to-be National League team known as the Bisons, where he would briefly manage. Mutrie would move on to a new, nearby team in Massachusetts, New Bedford.

New Bedford was run by Frank Bancroft, who was not a former baseball player like most managers were. He saw baseball as a business opportunity and treated his team like a touring performance group, and scheduled his team to play 130 games in 1878, far more than the few dozen many teams usually played in a year those days. Bancroft even scheduled a triple header on July 4th that was played in 3 different cities on that one day.

Bancroft was wildly successful financially, but Mutrie was not as a player under him, as he struggled to hit and field. Perhaps seeing Bancroft work led Mutrie in a new direction professionally. Mutrie followed Bancroft to Worcester in 1879, but was soon cut from the team. That led Mutrie to a new opportunity, as a team in Brockton, MA, offered him the position of manager. He led the team to the championship game, but as 1880 rolled around, he was focused on a bigger opportunity, one that anyone in baseball knew was sitting there. New York City.

The problem was, how to actually play there?

Before the 1880 season started, Mutrie tried to get an agreement to move the team in Brockton to New York, and join the floundering independent National Association (different from the original league). The problem was finding a field near NYC to play on. Mutrie initially focused on trying to move the team to Jersey City, and in March, he was seen in Brooklyn, scouting players with none other than William Cammeyer, the former owner of the New York Mutuals, and still the owner of the Union Grounds baseball park in Brooklyn.

Nothing came from that meeting, however, and Mutrie returned to Massachusetts, continuing to play and calling his team in Brockton “Jersey City” despite playing a few states away from it. The Washington Post made an announcement that Mutrie’s team would join the independent National Association, but play in Brockton until the Jersey City field was ready. But things were not materializing fast enough for the floundering team’s finances. In July of 1880, the Brockton team disbanded, and Mutrie took a job in a box factory in New York City.

However, Mutrie was not done with baseball. During 1880, Mutrie met a local business man, John B. Day, an amateur baseball player himself. The details of how the meeting are disputed, with the legend being that Mutrie approached Day after watching him pitch his team to a loss, and offering to build a new, better team. Another version is more simply that local sportswriters introduced the two.

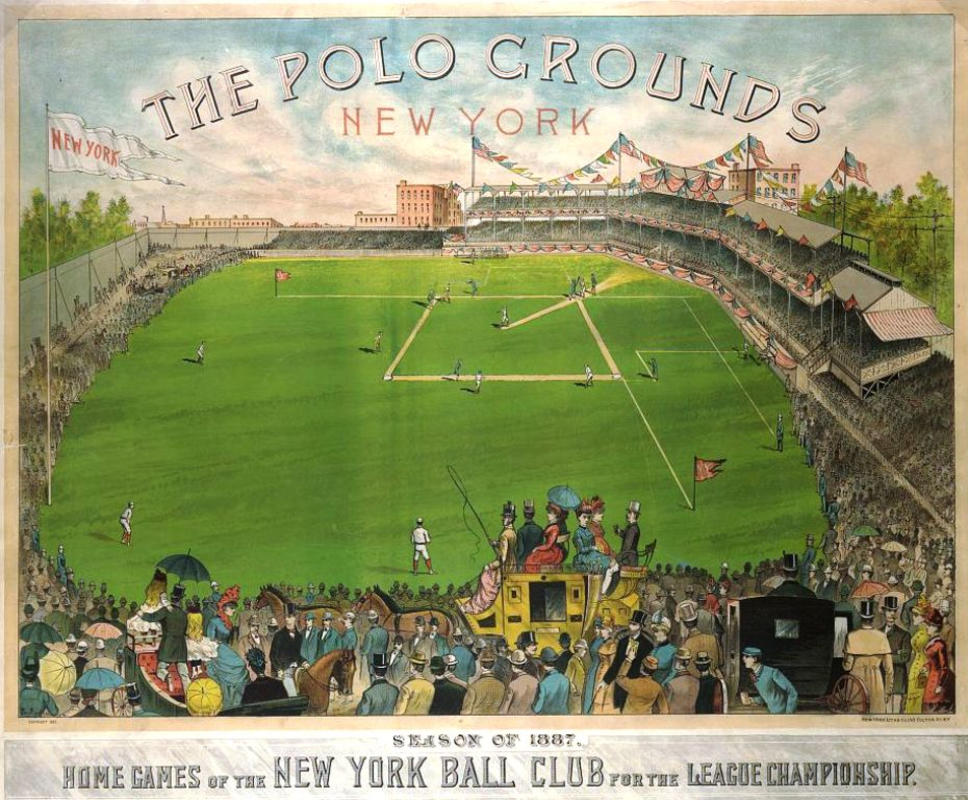

Whatever the truth about how the met is, Mutrie implored Day that he could put together a successful team, and was able to convince the businessman to partner with him. Day brought with him his business connections. He had connections to James Bennett, the son of the founder of the New York Herald, who had some land adjacent to the north end of Central Park, actually in Manhattan, that was more than twice as big enough for baseball. Bennett and his wealthy friends had used the land to play polo.

Day used his connections to convince Bennett to lease him the land, and Mutrie moved fast to put players together. By September of 1880, he had a team ready to play, and his new team made their debut in a hastily scheduled game, against the independent Unions of Brooklyn. Mutrie’s new team was named the New York Metropolitans.

The Metropolitans moved into the Polo Grounds on September 29th, 1880, playing the Nationals of Washington in the first professional baseball game that was actually played in New York City. They won, 4-2, in a game that ended early due to darkness.

The Metropolitans joined the Eastern Championship Association for the 1881 season, winning its championship, and was already playing exhibitions against National League teams, knowing the two Major Leagues would come calling.

*****

Baseball was not just stirring in Manhattan. Brooklyn had been the region’s true cradle of baseball. Most of the pro teams that had claimed New York as its home, including the New York Mutuals, had actually played in Brooklyn. The Union Grounds had been the game’s first enclosed baseball field where admission was charged. But like New York, Brooklyn had only had enjoyed small independent teams for the years since the so-called Brooklyn Hartfords folded.

Charlie Byrne, a former sportswriter who made money in New York’s booming real estate market, was well aware of the history and possibilities of baseball in Brooklyn. He knew Brooklyn was a booming market, and a new bridge would be opening soon to connect Brooklyn to its neighbor across the river. The pieces just needed to fall into place.

The first piece was George Taylor, the night editor at the New York Herald, the same paper whose founder’s son was leasing the home of the Metropolitans. Taylor had already leased land in South Brooklyn to build a ballpark on, but his partners had backed out. After Byrne met Taylor in 1882, Byrne brought in new investors to build a ballpark. He called it Washington Park, because it was on the site of the Revolutionary War’s Battle of Long Island, the first major battle for the Continental Army under George Washington. The site still had the Vechte-Cortelyou House, known mostly as the Old Stone House, which had been a key part of the battle. It would become the team’s clubhouse, where they changed and prepared for games.

With the stadium in place, Byrne rushed to get a team ready, knowing that both the American Association and the National League would be interested in a team in the most populous region of the nation.

*****

On September 28th, 1882, a Major League record was set that still stands today. The Troy Trojans hosted the Worcester Ruby Legs, in a battle of the two last place teams in the National League. They were witnessed by a record-low six paying spectators. Six.

That record for the lowest paid attendance still stands today, ignoring 2020’s cardboard cutout season.

Troy had been invited into the league by Hulbert four years earlier, but it was now clear that the National League had made too many exceptions to its own rule about city size. Meanwhile, the American Association’s Philadelphia Athletics would announce that they made a profit of $22,000 over the entire season, more than any team in the National League did.

The American Association was already on the move. The Association had already made an attempt in late 1881 to sign Mutrie’s New York Metropolitans to move into the big city. The Metropolitans had declined, since the team’s exhibitions against NL teams had been their most profitable games, and they would have to stop if they joined the AA. But the requests to join weren’t going to stop, and now the AA had proved they could turn a profit.

In the face of everything, and with Hulbert having passed away due to health problems, the National League owners were ready to return to New York City. A week before that notorious game, on September 22nd, the New York Times published the following note:

“The Executive Committee of the National League of professional base-ball players met today, and accepted the resignations from membership in the league of Worcester and Troy clubs. Applications for admission to membership from the Metropolitan and the Philadelphia Clubs were received, and will be acted upon in December.”

The battle was on for New York City.

The public record is filled with mixed messages, but behind the scenes, both the American Association and the National League wanted the Metropolitans. The team had been highly successful both in its minor leagues, and in playing exhibitions against National League teams. It had the only ballpark in Manhattan, and over the previous two years, the fans had come to see it as New York’s team. Committing to one league or the other would be a major decision not just for the team, but also for whichever league they joined.

So, over that winter, Mutrie and Day made a major decision: Why not join both?

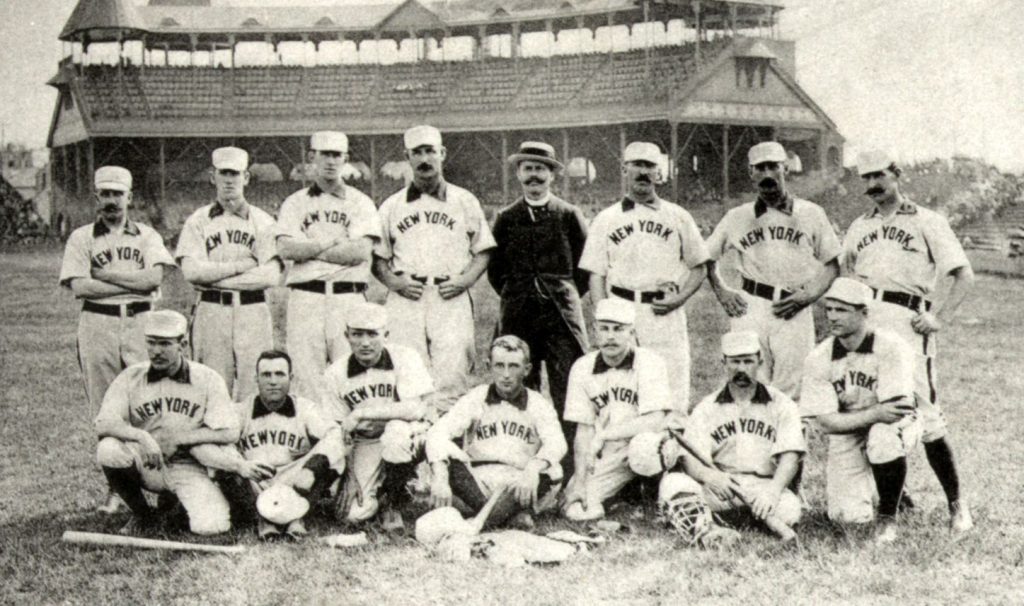

In November, Mutrie and Day announced that the Metropolitans would not be going to the National League, but would be going to the American Association. But they continued negotiating with the National League. Shortly thereafter, Day and Mutrie announced they would be also joining the National League. Not with the Metropolitans, but with a new team. After all, a polo ground is large enough for two baseball diamonds. The new team did not have a nickname, so the local media called them the New Yorks or the Nationals, both to refer where they played. The media would eventually substitute a nickname for New York as an unofficial nickname for the team: The “Gothams”.

The New Yorks and the new Philadelphia Quakers joined the NL, as Troy and Worcester were dissolved. While the popular story is that the Trojans roster would become the Gothams roster, Day and Mutrie signed just four players from Troy to New York: Mickey Welch, Buck Ewing, Roger Connor and Pete Gillespie. Three more former Trojans would find contracts with the Metropolitans: Tim Keefe, Bill Holbert, and Chief Roseman.

It was an impressive group to help found the new New York team. Three of those four players, Welch, Ewing, and Connor, would go on the be in the Hall of Fame, as would the Metropolitan’s new Tim Keefe. Connor would go on to the the Major League’s home run king, with 134 career home runs, which would stand until another New York player named Ruth would come along to break it by a fair amount.

Player movement like this, however, had become a concern for the two leagues. Poaching was a problem between leagues or even teams within the same league. Day and Mutrie were in a unique position, having courted both leagues, to speak to this, and needed the two leagues to co-exist.

In late November, Day would suggest an agreement between the leagues regarding both leagues respecting the “Reserve Clause” that teams had informally used for years to bind players to teams, which became part of the first National Agreement. It would not be written into contracts starting in 1887, but rules were set to stop teams from poaching players in the other leagues, by agreeing to not sign players who break their own reserve clause to try to leave a team. If a player’s contract expired and was not resigned, other teams had to wait 10 days before they could sign those free agents. This was to allow every team, from either league, to have an opportunity to court these free agents. This decision was an important step for owners on both sides to agree on player movement and salaries, but it also upset many players, and would have long-term consequences.

Across the East River, Charlie Byrne also had American Association aspirations, but the Association had added the Metropolitans and also expanded out west with the Columbus Buckeyes. There were no more spots open in the new league. Instead, the new Brooklyn team joined the Interstate Base Ball Association.

Despite getting a minor league team, the former cradle of baseball was ready for a new team. When the new Brooklyn team was able to debut in its new stadium at Washington Park, it drew a standing room crowd of 6,000 fans. By comparison, the home debut of the National League’s Gothams drew just 5,000. Although historians like to call Brooklyn’s team various nicknames like the Atlantics or Grays, referring to names of previous teams in the city, Byrne did not name the team, so the fans called the team whatever they wanted, including the “Polka Dots” because of the stockings the team wore in that first season.

Byrne was focused on the future, and expanding the team’s popularity and fortunes. He was even working so hard on expanding the team’s workforce that on the team’s home opener, he was hiring. He brought on board an assistant secretary and handyman by the name of Charles Ebbets. But Byrne’s hiring surge did not stop there.

Byrne got early word that another team in the Interstate Base Ball Association, Camden, was getting ready to fold. He was already talking to the Camden ownership before it folded, and despite managers from teams in both the AA and NL waiting to pick the bones and snatch away the best Camden players, Byrne got six of them to join Brooklyn. With the reinforcements, Brooklyn would cruise to a championship, with a 66-40 record in the Interstate Association.

On the island of Manhattan, the sibling teams of John Day began sharing their house. The Polo Grounds were split in two by a canvas fence. The National League team was still charging a pricey 50¢, as the NL still had many of the rules Hulbert had shaped, with no alcohol in the stands and strict rules against gambling and fighting. The American Association ticket price was only 25¢, but made their money off of the beer sales. That likely helped the decision to put the New Yorks in the existing grandstands at the east end of the Polo Grounds, and the Metropolitans moved to the west end, which was quickly constructed and was not quite as grand a stand.

Jim Mutrie continued to manage his established Metropolitans, with their new star pitcher Tim Keefe. Keefe’s 1883 season resulted in what was later calculated as a 20.2 Wins Above Replacement by Baseball Reference, which is the highest total for any player in a single season, ever. By comparison, Babe Ruth’s highest WAR in a season was 14.2 in 1923.

Despite Keefe’s monster season, the Metropolitan’s first year in the American Association ended with fourth place in the eight-team league at 54-42. The New Yorks, however, failed to gel as a team in their first season, finishing at 46-50, 6th place in the eight team National League.

*****

1884 was a big year for baseball in New York. The American Association, trying to fight off other upstart baseball leagues as well as the NL, decided to expand to 13 teams. That made it an easy decision to include a certain championship-winning team from Brooklyn. But it didn’t come without objections from across the East River. The Metropolitans tried to bar Brooklyn from hosting exhibitions against NL teams, thinking it would draw fans away from games in Manhattan. Mutrie made the argument at an American Association meeting in Baltimore, but Byrne’s logic won out. The Brooklyn Eagle commented that “Jim is devilish cute, but he has no business fooling with Byrne’s logical buzzsaw.” Byrne was so impressive, he was voted into the Association’s board of directors, where he helped set the league’s schedules.

The boardroom aside, the competition in the AA was much tougher for the Brooklyn team on the field. They struggled to a 40-64 record, finishing ninth in their first season as a Major League club. The New Yorks had a better season themselves, improving to 62-50, tied for fourth in the National League. But they were outshined by their siblings, who had tried to move out.

The western end of the Polo Grounds was not a great home, with a hastily built grandstand and poorer field conditions, so the Metropolitans tried to move away by building a new park a few blocks away. The land they found for this new Metropolitan Park, however, was a former dumping ground near factories, and it was quickly deemed “The Dump” by players and media. The reaction to the new site was not good by fans, media, or the players, and began playing more and more games at their old home in the Polo Ground, eventually returning for good in August. Despite not having a settled home field, Mutrie’s Metropolitans went 75-32, and won the American Association by 6 and a half games.

So Mutrie’s Metropolitans were champions of the American Association. The champions of the National League were the Providence Grays, who were led by a man that Mutrie knew well: Frank Bancroft.

In the years since Bancroft had managed the end of Mutrie’s playing career, his reputation had only grown. He had become known as one of baseball’s biggest heads for making money. Bancroft had taken the Worcester team that Mutrie had been cut from into the National League, and he’d also taken it on a tour of Cuba, which some credit as one of the important moments in developing baseball’s popularity in the country. He’d been lured to other teams due to his penchant for turning profits.

His ability to make money was partly from keeping player salaries low and fixed, and then working them as hard as possible, which chafed some of his players. In that 1884 season, the Providence team’s future became uncertain as players revolted, and their main starter Charlie Sweeney cursed out Bancroft on the field and left a game in the middle of it, and refused to report, in order to get himself fired and sign with a different team in one of the other, lesser leagues. Bancroft would be able to convince the team to stay together, mostly by turning to Sweeney’s rival on the team, pitcher Charles Radbourn, known as Old Hoss. Bancroft convinced Radbourn to pitch almost all of the team’s remaining games by paying him an extra $2,000 for the rest of the season, and granting him free agency at the end of the season. Radbourn was worth every bit of that deal, leading them to the NL Pennant.

With Bancroft heading that team, Mutrie had an idea. Mutrie challenged Bancroft’s Grays to a 5-game exhibition series, to be played in both cities, with a bet put up by both teams as a prize. Bancroft wasn’t interested in any prize, but he was interested in making money. He negotiated the series down to three games, all to be played in New York, where Bancroft knew there would be better attendance and wouldn’t have to pay travel costs, and the two teams would split the gate evenly.

Professional sports were still a relatively new thing in society, but for the most part in most sports, leagues were won by who had the best record in the season. For the first time, two teams would find out who was best on the field, in head-to-head games.

And it was Providence who was better. Led by Old Hoss Radbourn, Providence won all three games of the event. The media loved it, and would call it alternately “The Championship of the United States”, “The World’s Championship Series”, or simply “The World’s Series”.

*****

The precedent was set, and although the format would change with almost every year’s series, the tradition of two leagues having their champions face each other was set for the future. Baseball was the first North American sport to establish this trend, and through the following decades, nearly every major American team sport would adopt a similar method to determine their champion, whether between competing but equal leagues, or conferences within one league.

But the balance of the two leagues was about to shift, as 1885 rolled around.

The American Association’s expansion had been ill-advised, as not every team of its 13 survived even the full 1884 season. For the next year, it would be back down to eight teams, with Brooklyn and the Metropolitans easily making the cut as two of the regularly profitable teams. While the so-called Beer & Whiskey League was generally popular with fans, it was not necessarily being seen as profitable by the owners. Some teams in the AA began to raise ticket prices up to 50¢ for 1888, removing one of the few advantages the league had over the competing National League in drawing fans.

That doesn’t mean things were completely rosy in the National League. As 1884 was coming to a close, the National League’s Cleveland team was on the verge of bankruptcy. Brooklyn’s Charlie Byrne was on top of this opportunity once again. Now, however, he had to deal with the 10-day rule of the Major Leagues, where players could not sign for 10 days after being released, so that other teams would get a fair shot at negotiating.

Byrne went to Cleveland’s owners, and identified seven of the best players that he wanted. After the players agreed, he then took the players to a secret hotel, and they hid there for the new year. At 12:10 AM on January 5th, 1885, he signed all the players for an incredible total of $9,000, $5,000 of which went to Cleveland’s owners. The move set off a firestorm, but for all the talk of expelling Brooklyn, nothing came of it.

Meanwhile, in Manhattan, Day’s favorite child was the National League team, despite the Metropolitans’ on-field success. The new stadium site had been a failure, and the west side of the Polo Grounds were dingy, keeping attendance down. And the New Yorks were becoming more popular in the media, as the focus on middle-class values Hulbert had insisted upon paid off. Day wanted his NL team to win. And he wanted the best of his assets on that team.

Pitcher Tim Keefe and third baseman Dude Esterbrook were two of the Metropolitan’s stars. But if Day tried to move them, they were also subject to the 10-day rule that Day himself had helped implement. So Day and Mutrie thought it was time for a Spring Vacation. Day owned an onion farm in Bermuda, and on March 26th, Mutrie, Keefe and Esterbrook were seen boarding a ship for Bermuda. They were released from their contracts immediately after. When they returned after a 11 day cruise, they were already signed to the New Yorks of the NL.

The American Association was furious once again. They spoke of expelling the Metropolitans, but once again did not. They did, however, ban Mutrie from the American Association. That wasn’t much punishment, because he was now officially the manager of the National League squad.

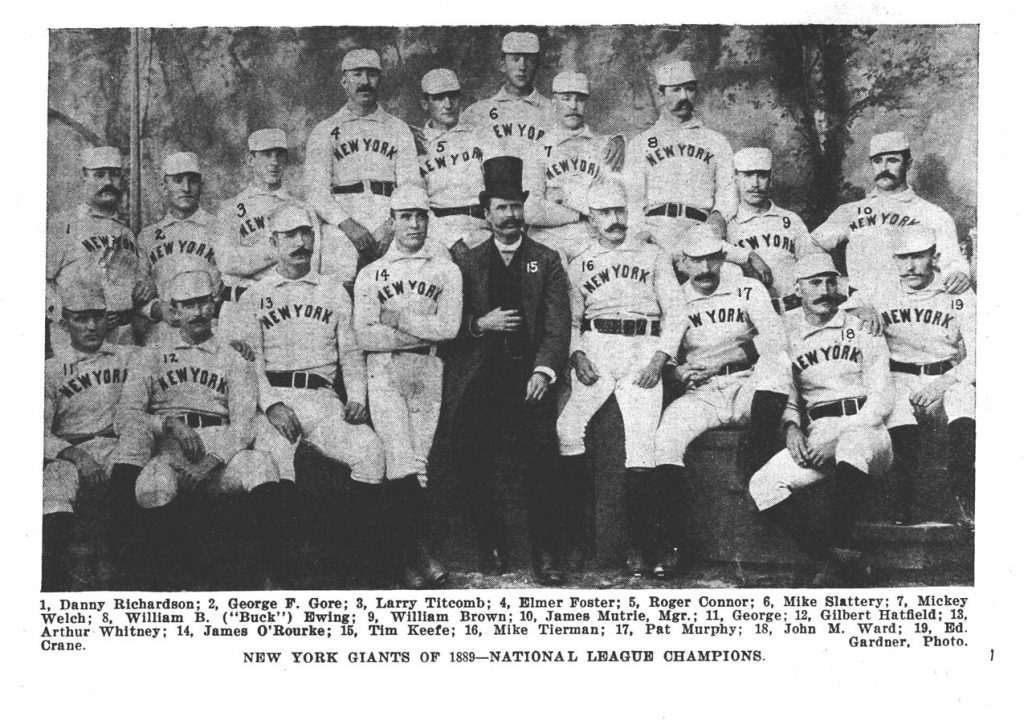

The Metropolitans, depleted, fell to 44-64, seventh in the American Association. Brooklyn floated around the middle of the Association, finishing tied for fifth at 53-59. But the New Yorks really redefined themselves in a couple of ways. One was their 2nd place record at 85-27, just two games behind the league champion Chicago White Stockings. The other was having a new name. The team had three players who stood over 6’4”, a rare thing in those days. Although the legend states that Mutrie walked into the clubhouse on June 3, 1885, after an extra-innings win and proclaimed “My big fellows! My Giants! We are the People!” and the nickname would catch on, local newspapers had begun calling the team “Giants” throughout the 1885 season, before this oft-reported quote supposedly happened. However it began, the name “Giants” stuck, replacing the informal nicknames like the New Yorks, the League Club, the Gothams, the Nationals, and even the Maroons (for the team’s colored trimming on their uniforms).

The AA’s 1885 champions, the St. Louis Browns, decided to continue the previous year’s post-season exhibition, and challenged the NL champion Chicago. It ended in a disputed 3-3-1 tie, with a Game 2 forfeit causing the split.

Before the 1885 season, the leagues were upset with their individual owners, but after the season, there was a different type of outrage. In October, the National League and American Association signed a new version of the National Agreement, with individual salaries being capped at up to $2,000. Days later, New York player John Montgomery Ward, a graduate from Columbus Law School, formed the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, the sport’s first union. Although the salary caps were never enforced, and players (including Ward himself) would make well above the cap, the union, and the frustrations behind it, would continue.

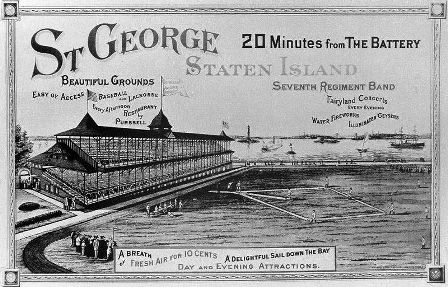

That winter, the Metropolitans were officially discarded by Day, sold to a Staten Island magnate Erastus Wiman for $25,000. The team moved a ferry ride away to Staten Island, although they kept the New York Metropolitans name.

The next two years saw both the Giants and Brooklyn flounder a little, but the Metropolitans truly suffered financially on Staten Island. Two years later, in 1887, Wiman was talking to Day about buying the Metropolitans back, as the astute businessman Day saw the opportunity for a profit if the price was low enough.

But on the other shore of the East River, Byrne saw an opportunity to help his team once again by buying assets and stick it to his cross-river rivals. With backing from his investors, he stepped in, and bought the Metropolitans, their players and their territory, for the same $25,000 that Wiman had paid two years earlier. Brooklyn saw four players they liked to keep, most importantly first baseman Dave Orr, a former American Association batting champ, and Darby O’Brien, a young outfielder with a lot of upside. The other players were sold off to the new Kansas City Cowboys of the American Association.

Brooklyn was not done with its spending spree, going on to buy players from the powerful St. Louis Browns, who were selling off some of their high-priced players after some had suffered small injuries. Byrne traveling all the way to San Francisco to personally sign some of them as the Browns were playing exhibition games there. There he got Al “Doc” Bushong, a veteran catcher, first baseman and pitcher Dave Foutz, but the biggest get was a star pitcher, Bob Caruthers.

Byrne also found himself a new manager: Bill “Gunner” McGunnigle.

McGunnigle had influenced the game himself as a player in the game. Early on in Fall River, McGunnigle had started as a catcher, with an arm so strong, his former manager said he had “a gun on his shoulder”, and the nickname stuck. McGunnigle was an innovator. As a catcher, he began using modified bricklayer’s gloves with the fingers cut off on his throwing hand, becoming the first recorded use of any form of a catcher’s mitt in baseball. He also helped develop a prototype baseball shoe with removable cleats after seeing how baseball shoes would tear up the carpets of hotels they stayed in. Now as a manager, he wore a suit (unlike most managers), and much nicer shoes than those cleats.

(It should be noted that one of McGunnigle’s new charges, Doc Bushong, improved upon’s McGunnigle’s catching gloves. Bushong is credited by many as developing the padded “pillow” catcher’s mitt, to protect his fingers as he intended to become a dentist after being a ballplayer.)

However, Gunner attempted other innovations as well that might not be as well-regarded with retrospect. When he would pitch, he used a thimble to cut the balls to help his curve. His attempts to affect baseballs didn’t stop there, as in the 1890’s as a manager, he would doctor a ball with rosin to make it dryer and easier to grip (this would become legal eventually). And as a manager, he explored methods using electric signs in the outfield to steal signs and signal the batter.

Whether his innovations for baseball were within or outside the rules, McGunnigle had some principles. When his 1885 team in Brockton began to fall into financial trouble and played poorly, the owners ordered McGunnigle to fine the players for the trouble and the blame. McGunnigle quit instead. Byrne offered McGunnigle the Brooklyn manager job for the 1888 season, but McGunnigle declined, as he had committed to manage the minor New England League team in Lowell for that season, after he had managed them to a league championship in 1887. Still, Byrne was a man who got what he wanted, and had the money to back himself up. Byrne negotiated with Lowell to release Gunner from his commitment. “Mac” came to Brooklyn, where he was popular manager among both the players and the fans.

But Brooklyn also began adding something else during that offseason. Four different players got married over the winter, which led to one newspaper correspondent saying “Now isn’t this a ‘bridegroom’ team?” Newspaper writers do love alliteration, and “Byrne’s Brooklyn Bridegrooms” stuck, even if some players did not care for it. The team, with all its new players, shot up the standings, and finished second in the American Association, 6 and a half games behind the St. Louis Browns, who had sold off some of their most expensive players but still won the pennant. St. Louis owner Chris Von der Ahe made sure to lord that over Byrne, as the two had formed a not very friendly feud within the American Association.

The Browns would face the New York Giants, who won their first National League title after trading for outfielder George Gore, the man Mutrie had talked into joining him with Fall River years before, and their team of stars had come together and were playing at their best. Day and the Browns owner Von der Ahe saw the possibility for profits, and tried to raise ticket prices to $1, but fan outcry changed their minds. The Giants went into that World’s Series against St. Louis and beat them in ten games (yes, ten games), 6-4, with star pitcher Tim Keefe starting and winning four of those games.

*****

As the 1889 season approached, baseball’s owners were working together with one common goal. They initiated something called the Classification Plan. The plan was that all ballplayers would be graded up ability, performance, and so-called “morality”, with A being the highest and E the lowest. Players would be paid standard salaries based on those very subjective grades, locked into no choice with the reserve clause. Many players hated it, but strike talk was quelled, with Day himself calling the strike talk “nonsense.”

Day had his own issues to deal with. The first was with his star pitcher Tim Keefe, who had asked for a $5,000 salary for 1889 after leading the Giants in 1888 through the World’s Series. Day only offered $4,000, the same salary that Keefe received in 1888. They stayed at a stalemate weeks into the season, until it was reported that Keefe said he would accept a compromise of $4,500 on May 9th. On the same day, notably, all the other Giants pitchers were reportedly sick or injured. Day accepted the compromise the next day, and Keefe returned to the field.

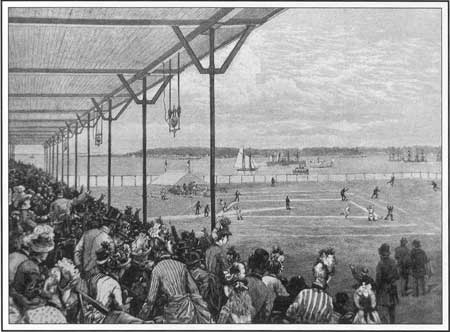

In addition to that, Manhattan had been growing, particularly growing northward, and the urban bustle had begun to envelop Central Park. The Polo Grounds sat on what was actually two blocks by the city plan, and the street that was supposed to go through the Polo Grounds, 111th street, had to be opened up. Day had to move his team, and he went further north, picking some of the last farmland on Manhattan in a place known as Coogan’s Hollow. Day called it the New Polo Grounds. The park would not be ready until the middle of the season, with the Giants playing games in Jersey City and Staten Island until the park was ready.

Before the 1889 season, Byrne went to Day, suggesting the two teams play three exhibition games before the season. Day was hesitant, but added “If you challenge my team, I will have to respond.” Byrne obliged. The three games were all played in Brooklyn, due to the closure of the old Polo Grounds, and the winner of each game to get all of the receipts from that matchup. The Giants took the first two games easily, but Brooklyn took the third, winning despite facing the superstar Keefe on the mound.

Although all the games were played in Brooklyn since the Giants had lost their own stadium, but the Bridegrooms were about to face their own problems at home. On May 19th, the grandstand at Washington Park caught fire, and burned down. The loss did not last long, however. With Brooklyn on the road, the club’s secretary Charles Ebbets was still in town. He was quickly on the scene, and vowed to Byrne to have the park ready for baseball soon. When the Bridegrooms returned on May 31st, the new stand was ready and fans were in attendance.

Ballpark drama aside, 1889 was one of the most exciting seasons yet in the history of the two leagues. For the first time, both leagues saw the pennant race come down to the final day. The Giants and the Boston Beaneaters were tied coming down the final day of the season, but Keefe won the final game of the season while Boston lost, giving the Giants their second straight National League pennant.

Once again in the American Association, the Bridegrooms fought a bitter pennant race with the St. Louis Browns, with allegations of dirty tactics hurled in both directions, considering Byrne had long been feuding with St. Louis owner Chris Von der Ahe within the American Association. But this time the Bridegrooms came out on top, edging out St. Louis for their first Major League pennant. The fans loved it, as Brooklyn’s full season home attendance of 354,000 fans was the highest for any team up to that point in history.

New York, the cities of Manhattan and Brooklyn, was home to both of the league champions. The two rivals who had competed for fans for half a decade would be facing off for bragging rights on the field.

Day and Mutrie met with Byrne to decide how to play this World’s Series, and they set another precedent for the future. Up until that point, each postseason series were played for whatever amount of games as had been decided upon by the two winners, whether or not one team had already won the majority of games. Two years before, Detroit and St. Louis had played 15 games in their World’s Series, with Detroit winning 10-5. Day and Byrne agreed to an 11 game series, but for the first time, the series would end once one team had won a clinching six games. With the teams so close to each other, geographically, they also decided to alternate games in each city.

On paper, the series was a mismatch. The Giants were defending champions, with a roster that included six future Hall-of-Fame players: first baseman Roger Connor, catcher William “Buck” Ewing, outfielder Jim O’Rourke, shortstop John Montgomery Ward, and pitchers Tim Keefe and Mickey Welch. No one on Brooklyn’s roster would make it into the Hall. Their biggest stars were Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz, who they had bought from St. Louis in 1887. The team had disposed of their biggest get from the purchase of the Metropolitans, Dave Orr, as he’d been a problem to the team’s chemistry, but they had held onto the much more fun-loving Darby O’Brien, who had been named McGunnigle’s on-field captain through the team’s tougher times.

While gambling was an ongoing problem for baseball in this era, former teammates Mutrie and McGunnigle had a wholesome bet: a new suit for the winner.

Game 1 was on October 18th, 1889, and took place in the new Polo Grounds in front of a crowd that overwhelmed Manhattan’s nascent rail car system. But it was the visiting Bridegrooms who struck first, against the dominating Tim Keefe. Darcy O’Brien and Pop Corkhill each hit doubles against the superstar pitcher to give Brooklyn a 5-0 lead after just the first inning. New York stormed back, taking a 10-6 lead in the 7th inning as John Montgomery Ward had a 2-run triple, and scored on a dropped fly to O’Brien.

Brooklyn came back to make in 10-8, and in the 8th inning with the skies getting dark, O’Brien redeemed himself with an RBI single, and scored to tie the game as a fly ball was lost in the dark to tie the game at 10. They would take a 12-10 lead as Dave Foutz hit into an error. The darkness was obviously becoming a problem. New York’s players began arguing for the umpires to call the game, which would’ve reverted the score back to the last full inning, when New York was up 10-8. Since there were two outs, Brooklyn’s Foutz stepped off second base, allowing Ward to tag him. That ended the inning, with Brooklyn up. Now the umpires would call the game to darkness, and Brooklyn won 12-10 in eight innings.

The scoring on Keefe was a surprise, and for unclear reasons, Keefe would only make one more appearance in the Series, in relief.

Game 2 in Brooklyn saw New York strike first against the opponent’s star pitcher, taking a 1-0 lead in the first off of Bob Caruthers. The teams would trade runs, ending up tied 2-2 after two innings, but the Giants broke through in the 5th. Ward knocked in a run with a single, and stole second on a poor throw by Brooklyn catcher Joe Visner. Ward took note, and danced off second to draw another throw from the catcher, and Visner obliged with a wild throw into center. That led to a 6-2 lead that New York held onto behind pitcher Ed “Cannonball” Crane. The series was tied at one apiece.

The action returned to Manhattan for Game 3, as the Giants struck in the first inning with a Buck Ewing RBI double, he stole third, and scored on a hit by John Montgomery Ward. But Brooklyn would jump out to a 6-2 lead after four. From there, the Giants chased Brooklyn, coming back but never quite tying the game until it was 8-7 in the 8th with the Bridegrooms ahead. McGunningle sent his star Bob Caruthers to pitch the top of the 8th, putting the Giants down in order, and in the bottom of the 8th, the Bridegrooms began to stall, playing very slowly, as darkness set. The Giants got to the top of the 9th and loaded the bases, but the umpires called the game for darkness at that point, and Brooklyn won 8-7, going ahead two games to one to the chagrin of the New York fans.

Cold weather that would plague the rest of the series began to set in for Game 4 in Brooklyn, but the Bridegrooms would be the first to strike again as Darby O’Brien walked, stole second, and came home on the errant throw trying to catch him stealing. That set the tone as Brooklyn jumped to a 7-2 lead by the end of the 5th, but the Giants would come back in the 6th to tie the game in a hotly contested inning. In the next inning, Oyster Burns hit a high fly to left field, and Giants left fielder Jim O’Rourke was unable to see the ball in the darkening skies. Brooklyn was up 10 to 7, and once again began to stall as things got darker. The game was called after six innings, giving Brooklyn a 3 game to 1 lead, as Giants fans, and others, complained.

After so many games being called to darkness with Brooklyn leads, and other calls deemed questionable, John Day began complaining and even impugning the umpires’ integrity, though each team had a hand to choosing the umpires for the Series. Charley Byrne brought Day, the umpires, and himself to meet. Day would apologize to the umpires, and the teams agreed to move the remaining games earlier in the day, starting at 2:15 pm, to ensure that darkness would no longer be a factor.

Game 5 was back in the Polo Grounds, the weather was cold again, and New York was down one of their best hitters as Buck Ewing was sick. But with Cannonball Crane back on the mound, the Giants got their momentum back. Once again, the Giants knocked around the Brooklyn star pitcher Caruthers, and the Giants took an easy 11 to 3 win, and were down 3 games to 2 in the best-of-eleven series.

Back in Brooklyn for Game 6, the cold weather was taking a toll on both teams. New York’s outfielder George Gore was out of the entire series thanks to a bad cold. Brooklyn had lost their catcher Bob Clark to a strained muscle, and had to put in a backup “Jumbo” Jim Davis at shortstop as their regular Germany Smith missed the game, reportedly due to a hangover. The weather likely also had a hand in the scoring, as the game was held to a 1-0 Brooklyn lead through the 9th inning.

With 2 out in the 9th, John Montgomery Ward came up for the Giants, in a plate appearance that could have swung the entire series either way. With a full count, Ward slapped a single to right field. On the first pitch, he stole second, and on the next pitch, he stole third, taking advantage of Brooklyn having backup Joe Visner at catcher. Roger Conner, who led the team in RBI, was at the plate, and he hit a grounder towards Davis at shortstop. Davis kicked it, and Ward scored to tie the game. The game went to extra innings, and Ward came back to the plate with a runner on second. Ward hit the ball towards Davis at short again, and beat out the throw. The runner on second, meanwhile, took advantage of the close play at first to keep running, and came home, beating the throw there, and the Giants won 3-2, and had tied up the series at three games apiece.

Brooklyn manager McGunnigle made a change to his plans in Game 7, as the Giants had been beating up on his star pitcher Bob Caruthers, and replaced him with one of the team’s other pitchers, Tom Lovett, to start the game. But New York was now on a role, and the Giants put up 8 runs in the second inning against Lovett before Caruthers was called in for relief. The Giants won 11 to 7 in Game 7, and then blew away Brooklyn’s starter Adonis Terry for a 16 to 7 win in Game 8. The Giants had won four straight games, and led the best-of-eleven series 5 games to 3.

Game 9 came back to the Polo Grounds, with the series on the line, and Brooklyn tightened up their game. An Oyster Burns double in the top of the 1st inning scored two runs, and New York scored a run on John Montgomery Ward’s triple to make the score 2-1. Unlike the high scoring affairs of the past games, the 2-1 score held until the 6th inning. Once again, Ward led the charge for the Giants, hitting a leadoff single, was knocked over to third, and scored on a sacrifice fly to tie the game. In the 7th, with a runner on third, New York’s Buck Ewing was at the plate with a full count. He would strike out swinging, but Brooklyn’s backup catcher Doc Bushong let the pitch get by. The runner scored, and New York had the lead, and it would hold on for the 3 to 2 victory.

The New York Giants had won the 1889 World’s Series, defeating Brooklyn, 6 games to 3. Fans at the Polo Grounds celebrated, chanting “We are the People!”, the battle cry that Mutrie had coined.

*****

1889 was almost the end of the beginning chapter of professional baseball. Over the previous decade, the Giants and would-be Dodgers were born, overcoming odds through good play, big spending, and some rule-subverting moves. And by the end of it, the two teams were cemented rivals. The National League had survived its struggles, and met the challenge of a rival league. And baseball as a sport had evolved.

The 1889 World’s Series also was an important financial success. Despite a cold spell, the 1889 World’s Series attendance in nine games exceeded the 1888 series attendance in ten games, and total profit for the 1889 series nearly doubled what the teams made in 1888.

But with 1890 came the end to that era. Everything was about to change.

John B. Day was a very good and very profitable businessman. But his and the other owners fixation on profit and cutting costs had finally pushed the players too far. The first attempt at a player’s labor union, the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, had been upset with the ownership of both leagues for a while, but the Classification Plan had been the last straw.

Only six days after the end of the World’s Series, the players created their own league, the Players’ League, with droves of players from both the NL and the AA. Leading the charge was the Giants’ John Montgomery Ward, and nearly all of the Giants stars left with him.

The new Players’ League set itself to play in opposition to the other leagues as much as possible. A new New York Giants club was born in the Players’ League, with many of the old Giants, and they also picked up land in Coogan’s Hollow, building their own stadium, Brotherhood Park, next to Day’s older new stadium. John Montgomery Ward would head up a team in Brooklyn, Ward’s Wonders.

In the American Association, St. Louis Browns owner Chris Von der Ahe was tired of his Brooklyn rival’s high-spending ways and willingness to bend the rules to acquire players, despite his own disreputable reputation. In the offseason, he put together a group of team owners that would take control of the A.A. They would nominate from their own owners to be league President, and block anyone from Brooklyn, or other controversial teams like Cincinnati and Baltimore, from being on any Association committees.

In November at a New York hotel, the two sides held a meeting, and voted. The eight team league was deadlocked at 4-4. They voted 34 times over the next two days, and remained deadlock. Byrne left the meeting with one of his allies, Aaron Stern of Cincinnati, and went down the hall. It turned out that the National League was holding its meeting in the same hotel. A little later, Byrne and Stern returned to the AA’s room to tell the other owners that they had resolved the deadlock.

The Brooklyn Bridegrooms and the Cincinnati Reds, the team whose expulsion led to the American Association, would join the National League.

In response, the AA tried to set up their own Brooklyn squad for 1890, the Gladiators, to have a presence in the New York area. However, that put five teams in the New York area: the two Manhattan-based teams calling themselves the Giants, the Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the NL, the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders from the PL, and the AA’s Brooklyn Gladiators. The Gladiators were first to falter, folding by midseason. But the New York area still had four teams that clashed with each other for fans all season.

In the past, the League and the Association had created schedules so one team in New York would not be at home with the other team was. This year, the Player’s League intentionally scheduled against the National League’s home games. With most of the stars in the PL, it hit the NL Giants hard.

On the field, the NL Giants squad was decimated, with just three players returning from the 1889 championship season, and after Day and Mutrie picked up the pieces of a dissolved team from Indianapolis, the Giants finished 6th of the NL’s eight teams. But the Bridegrooms came out on top of this chaos. They won the National League in 1890, and went on to face the American Association’s Louisville Colonels in the World’s Series. They agreed to a best-of-7 series. They played all seven games, with Game 3 ending in a tie, and the series ended 3-3-1. By then, the weather had turned sour, and the two teams agreed to meet the following spring for a deciding game.

But that deciding game never happened.

*****

Three leagues were just too many for professional baseball, and bitterness from the feud changed everything. The Player’s League lasted only one year, but its existence, and the anger about the issues that had prompted its existence, had devastating effects to the National League, particularly to the New York area clubs.

While the Bridegrooms had won the pennant, they had suffered financially. When the backers behind Ward’s Wonders came to merge with the Bridegrooms, Byrne and his ownership group agreed. But the new group wanted John Montgomery Ward to manage the new team, replacing popular Gunner McGunnigle, and also wanted the team to play at Eastern Park, a more remote stadium that was surrounded by trolley lines that fans would have to run through to get to games. Byrne capitulated to both conditions, and the Brooklyn team would suffer for attendance at the new park. Byrne would stay on in both with the ownership group and the leadership of the National League for several. Byrne passed away in 1898, but was succeeded in the role of team president by his former club secretary and handyman, Charles Ebbets, who would fight to keep the team in Brooklyn over the next several years.

In Manhattan, the NL had won in terms of surviving, but the struggling Giants had to merge with their Players’ League competitors from a position of weakness. The owner from the Player’s team, Eddie Talcott, took control of the Giants with a strong hand. He moved the old team to his new stadium next door, renaming his Brotherhood Park the Polo Grounds (making it the third stadium to have the name), and gave the old new Polo Grounds the name of Manhattan Field. It was used not for baseball anymore, but was used for other things like track and horse racing. Jim Mutrie stayed on, thanks to Day’s insistence, but his power was undercut, and Mutrie was dismissed in 1891. Day remained team president for another year after that, but his power was almost entirely gone. Day retired in 1893, retaining a small ownership stake, and would stay on the periphery of baseball the rest of his life, although he did serve as manager of the Giants for half of a season in 1897 after being offered the role by a friend in the organization. He was quickly fired when he did not post a winning record. Both Day and Mutrie were out of baseball entirely, as the sport moved on without them.

The American Association survived the Player’s League revolt, but after most of the Player’s League teams joined with National League franchises, there were renewed bitterness and struggles between the two leagues. The two leagues did not schedule that final championship game from the 1890 Brooklyn and Louisville World’s Series, and there was no series played in 1891 between the winners of both leagues, the Boston Beaneaters of the NL and the Boston Reds of the AA (a team who had come over from the Player’s League). So the 1890 World’s Series, the last of the championship exhibitions between the NL and AA, ended, fittingly, unresolved in a 3-3-1 tie. The American Association folded after 1891, and some teams, including Von der Ahe’s St. Louis Browns, jumped to the NL.

The National League was alone once again, and it struggled through the 1890’s even though it had a monopoly on major league baseball. In 1894, they began a new attempt at a postseason exhibition by dividing the season into two halves, and having the first half champion play the second half champion for the newly-created Temple Cup. That series lasted only 4 years. The New York Giants won the first Temple Cup, but it was the Baltimore Orioles who dominated the Temple Cup era, appearing in all four Temple Cup series, winning two of them. The Orioles were led in part by their fiery third baseman, John McGraw.

After 1899, four more teams from the National League dissolved, leaving the league with only eight teams. Not long after, they would soon be challenged once again by a new league, once again led by a strong-minded businessman who, ironically, felt that the National League environment was too rowdy and abusive, and needed to set a better environment for more fans, especially women and families, to enjoy. But the lessons learned from the 1880’s was the precedent that led to an agreement that allowed the National League and this upstart American League to compete and also co-exist. Of course, they still exist today.

Those eight teams that survived the 19th century still survive today. Since 1900, no Major League Baseball franchise has ever folded. They were known as the National League’s Classic Eight: The New York Giants, the Cincinnati Reds, the Chicago Orphans (who became the Cubs), the St. Louis Cardinals (formerly the Browns), the Boston Beaneaters (who became the Braves), the Philadelphia Phillies, the Pittsburgh Pirates, and the 1900 pennant winning Brooklyn Superbas (who, of course, became the Dodgers). These Classic Eight were the foundation of baseball to come.

Not all the men in these stories are all heroes or were always good people. They set the rules, and then did everything they could to break them or get around them. Many supported policies that were distasteful, from the gentleman’s agreement that kept black men out of baseball, to the enforcement of the reserve clause, tying players to one team and keeping salaries low…both issues that have caused strife and interrupted and embarrassed baseball throughout its history.

But these were the people that made baseball what it is today. And when we watch the Giants and Dodgers play today, it’s not just their rivalry, but it’s part of the story of baseball itself, and how it became the game, the sport, and the industry it is today.

*****

People say that the magic number in baseball is three. Three strikes and you’re out. Three outs in an inning. And so many numbers in the sport that are multiples of three…Nine innings, 90 feet down the basepaths, and so on. But I disagree; three is not the sport’s magic number.

I think baseball’s most important number is two. Two teams playing against each other. Two rivals.

Rivals are two of the same, competing with each other. They make each side have to be better. The Giants and Dodgers didn’t start as rivals. They each had their own rivalry with the Metropolitans, whether it was the Giants sharing owners and ballparks, or the Dodgers competing in the same Association as them. As the Metropolitans faded out, the Giants and Dodgers turned to rival each other.

But the concept of rivalry goes beyond the teams. In the 1870s, some people, like Bancroft, treated their teams as traveling performers, like a group of actors performing from town to town. But when Mutrie called up Bancroft to challenge him to the first World’s Series, the two men had a history to play off of. When New York and Brooklyn faced each other in 1889, the fans of both teams, of both future boroughs, wanted their team to prove their home was better, and they came to watch.

The National League and the American Association started as a feud, with competing viewpoints as to what baseball and its fans were, and what they should be. But when the two sides learned to work with each other, to play against each other, baseball was better off for it. Feuds can tear things apart, but rivalries can make things better. And so, when the American League was established, all of baseball knew how to work together, even as rivals.

The rivalry between the Giants and Dodgers was born in the 1880’s, and has stood through the decades. And, ironically, these two teams that were formed in a vacuum because two teams didn’t want to travel west, became the two teams that together would move baseball all the way west, to the west coast. And though the teams and fans each celebrate the moments of beating their rivals, from fan chants to savage social media posts, the teams still work together on the more important things beyond baseball, such as taking a knee together in the stand against racial injustice.

Rivals. 132 years later, Major League Baseball does not consider the games played between the National League and American Association to be official postseason games. For 65 years, the only postseason was the World Series, which is why those tiebreakers in 1951 and 1962 tiebreakers were considered regular season games, and why tradition means future tiebreakers still are. It wasn’t until 1995 that there was even the chance for a meeting between the Giants and Dodgers in the playoffs.

One could say this 2021 Divisional Series is less important than 1889, when they played for a World Championship. You might have an argument to say that even those two tiebreaker series were more important than a Divisional Series, since those tiebreakers declared who would be going to the World Series.

But there is only one important playoff series at this point: The one we are about to watch. None of that history matters when the teams take the field. Two rivals. One winner.

The Giants and the Dodgers. Playoff baseball. Are you ready?

Resources:

The Society of American Baseball Research

When the Dodgers were Bridegrooms: Gunner McGunnigle and Brooklyns Back-to-Back Pennants of 1889 and 1890, Ronald G. Shafer, 2011

The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants, Noel Hynd, Nov. 2018

Special Thanks to The New York Times

Recent Comments